2023 Farm Bill Presents Opportunities for Farmers and Ranchers on the Frontlines of Climate Change

By Elizabeth Tobey and Gordon Merrick

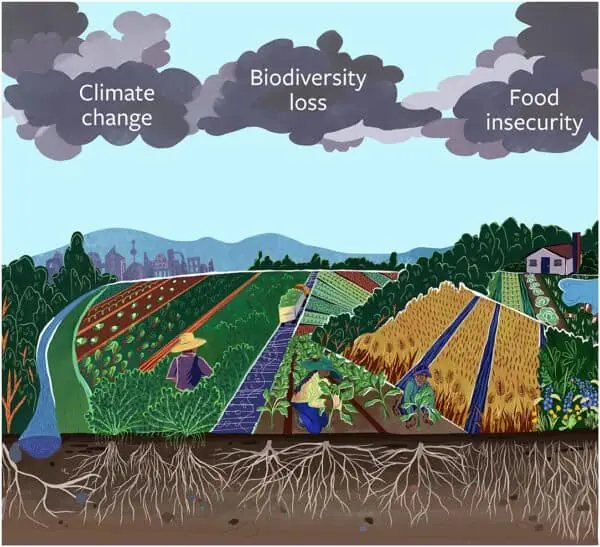

Farmers and ranchers, the people who produce our food, are often on the frontlines of challenges facing our society. Among the most pressing of those issues is the changing climate and an industrial food system that prioritizes profits over the health and wellbeing of people and the planet. Combined with the unprecedented loss of biodiversity, these three issues have even been called a triple threat to humanity.

Image from Frontiers article “Narrow and Brittle or Broad and Nimble? Comparing Adaptive Capacity in Simplifying and Diversifying Farming Systems”

These challenges are interrelated. The current standard methods of conventional food production are an outgrowth of the technological and chemical advancements of the mid 20th century, which resulted in a rapid increase in the ability to export calories in the form of commodity crops, such as corn and soy. This production depends on the ubiquitous use of cheap agri-chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and continued expansion of farmer-debt (as discussed in this article and this article) to increase scale and maintain technological relevancy. This ‘get big or get out’, petroleum-dependent production system decreases biodiversity and weakens the landscape’s capacity to be resilient and adapt to our changing climate. It also makes our food system vulnerable to even slight shifts in things like crop production or labor availability.

Farmers often keenly feel the challenges presented by warmer temperatures, increased flooding, and other extreme weather events. Caroline Baptist is the owner of the River Valley Country Club, a small farm in Washington state. “Farming on a floodplain and a floodway can be a challenge, and changes in climate over the years have only exacerbated this issue,” Baptist says. “The property owner from whom I lease land remembers experiencing 1-2 major floods a year when he first began farming in the area in 1993. More recently, we’ve seen these numbers double and triple.” Describing a recent flooding event Baptist says, “Some areas of the farm were under water by 15 feet and accessible only by canoe. This flood and every flood since is a sobering experience, illustrating clearly that the climate crisis is real, and it affects farmers firsthand.”

Past farm policies that favored the ‘get big or get out’ model led to increases in monocultures. The resulting abundance of commodity crops in the food system correlates with increases in processed foods, and associated adverse health effects in low-income and systemically underserved communities (more on that here).

SCF Organics brings fresh produce to people experiencing food deserts.

Shaheed Harris is the farm manager at Sumpter Cooperative Farms (SCF) in South Carolina. Among many other endeavors, SCF runs the Midlands Organic Mobile Markets, which are a suite of vans that directly distribute locally grown organic foods to the food deserts in the Midlands region of South Carolina. This project aims to address the need for equitable food access in communities in nearby metro areas with limited access to healthy foods. “Those places are areas … where they don’t have a grocery store,” Harris explains. “A lot of people don’t have vehicles to drive and they’re basically living on the nearest equivalent of a gas station. So they’re eating out of a gas station and getting chips and all types of processed foods that don’t really have a lot of nutrition.” Through the Midlands program, Harris says SCF aims to serve the people in these areas who would not otherwise have access to fresh healthy foods.

The farm bill is a package of legislation, updated once every five years, that sets the stage for our food and farming systems. The current farm bill expires in October of 2023, and a new suite of legislation will be developed and put into action. This farm bill cycle is a ripe opportunity to make solid advances towards a just transition to a new type of production that both mitigates and adapts to our changing climate, supports the health of the land and the people producing our food, and can help prevent food insecurity by increasing the amount of organic, nutritious food on American’s dinner plates.

Because of their place on the front lines of these challenges, farmers and ranchers represent a vibrant space of innovation and creativity to meet them. Our farmers and ranchers answering these challenges should be sources of inspiration on policy tools and instruments for the 2023 farm bill.

Clover cover crop, to be tilled back into the soil.

Jesse Buie is the president of Ole Brook Organics in Mississippi. One of the main environmental factors that Buie deals with is a lot of rain which can cause leaching of nutrients from the soil. To combat this he focuses on building healthy soil by making sure that he is constantly adding organic matter. At Ole Brook Organics they do this primarily by incorporating all the plant matter back into the soil. Any grasses or crop residue left after a crop is harvested are chopped up and tilled back into the fields, forming a closed-loop of nutrient cycling.

At SCF Harris is dealing with the opposite environmental concern: too little water. They have addressed this challenge by implementing Dry Farming practices that he learned from his family’s farming heritage. This style of farming, which combines unirrigated crop production with shallow cultivation offers a promising alternative in times of uncertain water resources.

Building resilience to economic disruptions has led some farmers to increase their use of local inputs, processors, and distributors, avoiding or lessening the impacts of supply chain disruptions in global markets. And as an added benefit this localization increases the access to nutritious, culturally appropriate, and tasty food that can connect communities.

Rotational grazing can be a tool for healthy pasture management.

Dayna Burtness is a farmer at Nettle Valley Farm in Spring Grove, Minnesota, raising pastured pigs. “We’ve been able to build community while building land resiliency,” she explains. “We’re able to work with nearby farmers and fruit growers to take non-marketable produce and turn it into delicious pork, which is benefiting everyone! It reduces the amount of food waste and helps other farmers put what they grow to good use. We are working hard to help create a different type of food system, we just wish there was more public support to really kick this change into overdrive.”

Federal research, conservation, and market development programs created and funded in the Farm Bill make all of these things possible, but expanded support is necessary to continue to support farmers and create a healthier future for people and the planet. If you want to get involved in advocating for a better food system, Ariana Taylor-Stanley (ariana@sustainableagriculture.net) at the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition or Gordon Merrick (gordon@ofrf.org) at the Organic Farming Research Foundation!

. . .

Links for further reading:

Green Revolution: History, Impact and Future, by H.K. Jain, available through most book suppliers

Chicken farmers say processors treat them like servants, AP News

Farmers and animal rights activists are coming together to fight big factory farms, Vox

2021 Tied for 6th Warmest Year in Continued Trend, NASA Analysis Shows, NASA

The 2010s Were the Hottest Decade on Record. What Happens Next?, Smithsonian Magazine

Americans are eating more ultra-processed foods, Science Daily

Ultra-processed foods and adverse health outcomes, The BMJ

Examining the Impact of Structural Racism on Food Insecurity: Implications for Addressing Racial/Ethnic Disparities, National Library of Medicine

Black, Indigenous, and People of Color Community at Disproportionate Risk from Pesticides, Study Finds, Beyond Pesticides

Equitable Access to Organic Foods: Why it matters, Bread for the World

What is the Farm Bill, National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition

Hunger and Food Insecurity, Feeding America