A Farmer Panel recap from the Transitioning to Organic Farming Conference at the Eastern Nebraska Research, Extension, and Education Center in Ithaca, NE

By Brian Geier, OFRF Communications Manager.

“I used to write checks to chemical companies. Now I write them to my kids,” explains Tom Schwarz, a 5th-generation farmer from southern Nebraska, while discussing the advantages of organic production. The Schwarz Family Farm has been farming organically since transitioning the farm in 1988. Along with his wife and two kids, Tom raises corn, soybeans, wheat, field peas, alfalfa, oats, and numerous cover crops. He was speaking at the Transition to Organic Farming Conference hosted by the University of Nebraska, Lincoln, alongside two other organic farmers.

As may be the case for many farmers in rural Nebraska, farming is not new to any of the organic farmers on this particular panel. Each spoke with a familiarity and vocabulary that comes with decades of experience. All three of them are from families who are farming hundreds or thousands of acres, some owned, many rented, in various stages of leases. And all of them had, at some point in the past few decades, switched a portion of their farming enterprises to certified organic production. For these farmers, who carry on family legacies of farming that survived the farm crises of the 1970s and 80s, organic is, among other things, a way to survive. It is also a path toward passing a farm operation onto the next generation that is better, safer, and more profitable than when they started.

No-till, organic corn at Young Family Farm in Nebraska. Photo credit: Barry Young, farmer-presenter on the “Organic Production: Nebraska Growers’ Perspectives” panel.

Like most farming, organic is not all easy. Tom presented what he sees as the disadvantages of organic: it is management-intensive (more machinery passes per season), requires extra recordkeeping, and WEEDS (emphasis via capitalization added from Tom’s presentation). “It’s just plain harder,” he explained, citing the need to be able to adapt on the fly and to creatively problem solve.

Matt Adams, who started farming with his dad in 2016 and operates about 600 acres in Seward, Nebraska, also spoke on the panel. He agreed that there can be difficulties with the transition to organic, particularly with having machinery settings or setups needed for larger-scale grain production. “Get everything ready way before,” he warns, “so the day you need to be out there, you’re ready.”

Matt transitioned non-irrigated land that was previously in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) to organic hay and row crops. Since the fields were in CRP, there had been no prohibited substances applied to them, and they were ready to certify, meaning he did not have to steward them through the three-year transition period to organic. But since the land had not been fertilized or cultivated, Matt is finding that yields have been low and weed pressure high, putting extra strain on the need for timely, effective cultivation setups.

When addressing challenges, the number one source of information for organic farmers is other farmers. And Nebraska’s organic farmers on this panel are no exception.

“I do have some original thoughts. But I always throw them to the wolves first,” explains Barry Young, the third panelist who operates Young Family Farm in southeast Nebraska. “I should call it ‘Young Community Farm’”, he chuckles, giving credit to past mentors that first taught him about polyculture planting, and acknowledging fellow farmers and family members that he discusses ideas with before trying them. Barry finds that sourcing inputs is one of his biggest challenges. Despite living in farm country, “No one around me was doing what I’m doing,” he said. Still, by persistently asking questions of fellow organic and regenerative farmers, who he finds are more apt to share knowledge than many conventional growers, he has learned to meet main challenges like developing inter-species planting mixes for weed control.

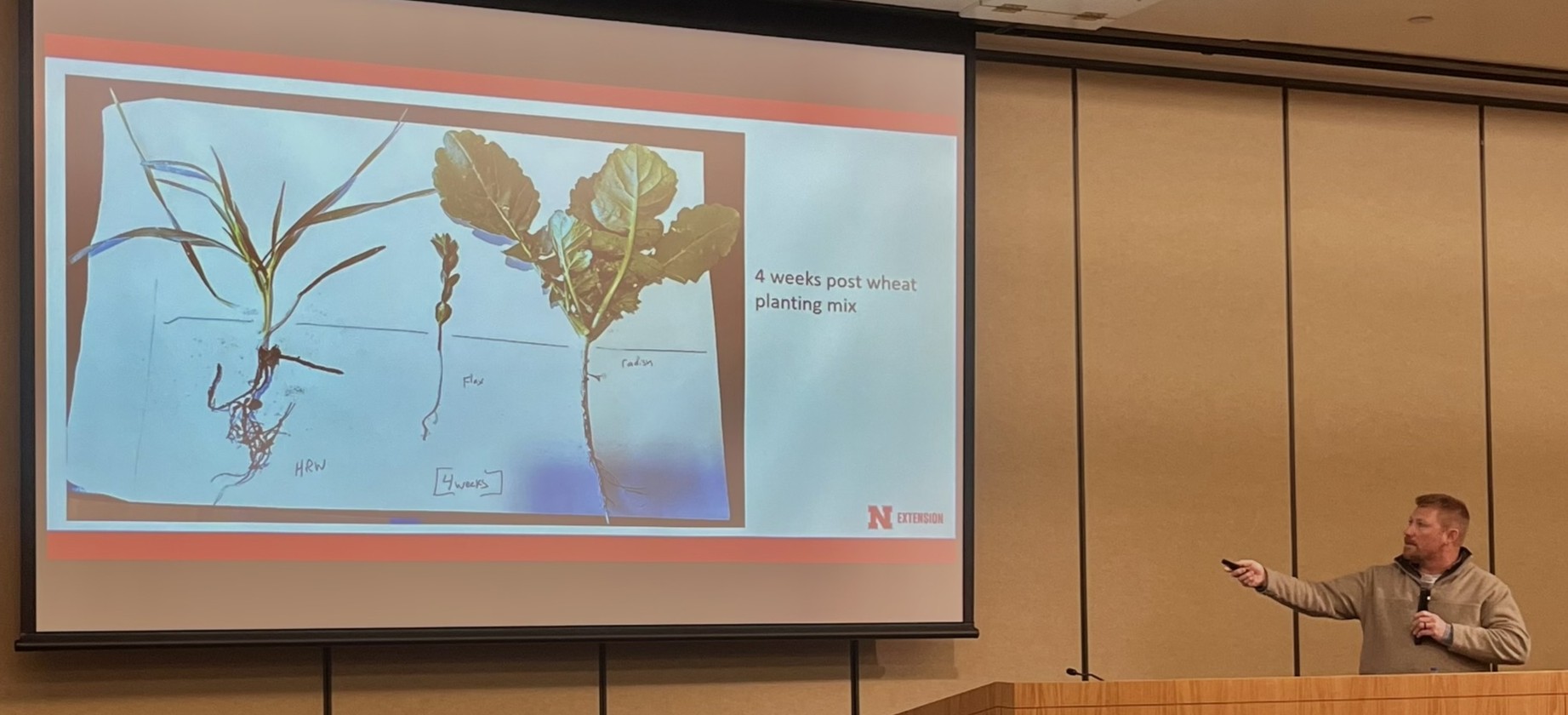

Organic farmer Barry Young explains his polyculture planting mix for organic wheat, which includes a custom mix of 120 pounds of wheat with 2 pounds of radish and 3 pounds of flax. The flax, a legume, helps enhance the soil microbiome while the radish helps break compaction especially following alfalfa. Both winterkill and the wheat matures as a pure stand for harvest the next season.

Earthworms and good soil structure in a November cover crop at Young Family Farm.

A high biomass (10-ton per acre) pea/oat cover crop following no-till corn planting at Young Family Farm

Corn grows with a soil-building mix in wheat stubble at Young Family Farm.

Secondary roots on organic, no-till corn at six weeks post-emergence at Young Family Farm.

“This is the way we’re intended to farm.”

-Nebraska organic farmer

All three of the farmers spoke about several advantages of organic production, too. One described lying down in a field, observing the increase in bug and bird life following the switch away from pesticides, and thinking, “This is the way we’re intended to farm.”

Other advantages cited include organic’s market stability, and the regional control and accountability within the market chains. With organic grain production, many farmers are selling niche crops to regional processors who are then selling food back to the community. This creates a market and economy that farmers form long-term relationships with, and it stands in contrast to the volatility and lack of accountability from larger, conventional commodity crop markets where crops are shipped out of state or country for processing. It is “consumer-based as opposed to commodity-based,” Tom points out.

But ultimately, for Tom and others on the panel, it is about their farms’ future, and that is about the quality of life of the next generation. Today, there are challenges with organic, for sure, but farming has been a difficult profession for generations of Nebraskans. With organic production as at least a part of the farm, Tom feels he is creating something that will be passed on to the next generation and be better than what he inherited. Aside from now being a paid part of the organic operation, Tom notes that “The kids will not be exposed to chemicals like I was,” adding, matter-of-factly, “that’s the biggest reason I do it.”

For Plains farmers interested in learning more about the USDA’s National Organic Program, we encourage you to explore resources and upcoming events hosted by the region’s Transition to Organic Partnership Program (TOPP). You may also want to explore OFRF’s step-by-step guides, printable tools, and farmer experiences to help you access USDA programs and funding, such as the NRCS’s Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) and the RMA’s Whole-Farm Revenue Protection (WFRP) program.