Balancing Act: How Frog Song Organics Integrates Livestock and Crops

When John Bitter and his wife Amy started Frog Song Organics on 5 acres in 2011, a vision of how to carefully scale-up the farm was long in the works. They both had several years’ experience working with farms in the area, and each knew nearby markets well enough to know they had opportunities to grow. Looking ahead, they had also spoken with the owner of neighboring land about leasing additional acreage in the future.

Fast-forward 12 years, and Frog Song Organics is a 62-acre operation with about 30 full-time employees and 20-40 acres in production at any one time. Located less than a 2 hour’s drive from several markets, Frog Song provides organic products year-round to four farmers markets and wholesale accounts in Gainesville, Orlando, St. Augustine, and Tampa, and through an online-order, customizable-box CSA program.

Fast-forward 12 years, and Frog Song Organics is a 62-acre operation with about 30 full-time employees and 20-40 acres in production at any one time. Located less than a 2 hour’s drive from several markets, Frog Song provides organic products year-round to four farmers markets and wholesale accounts in Gainesville, Orlando, St. Augustine, and Tampa, and through an online-order, customizable-box CSA program.

At this stage, John is happy with the size of the operation, and focused on improvements to the overall farm. “Now we’re just trying to fill in the efficiency of what we are doing. We don’t really want to get a lot bigger but we want to get more efficient and more profitable, being able to do more with less resources, essentially,” he said.

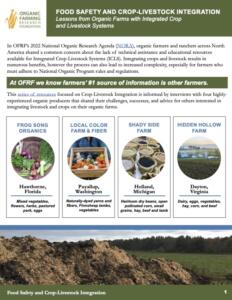

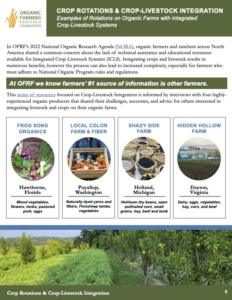

Frog Song is a highly diversified farm producing vegetables, herbs, flowers, orchard crops, pork and poultry products, and legumes. For John, balancing the livestock and crop enterprises is key. “Something to think about is how all this scales,” he said. From his perspective, scaling “needs to match the fertility, the planting, and the marketing…and if one of those is way out of whack, the business might fail.” So while Frog Song could produce a lot more pork and eggs, keeping a system that is balanced, where the amount of livestock fits the crop systems, is John’s recommended strategy. “People are looking at one way or the other, like ‘I’m going to be a pig farmer or a chicken farmer’, well, that’s 1/8th of what you do, or 1/12th of what you do, and you base the rest on what grows really well in your area and what resources you already have available rather than trying to bring in too much of the resources that will end up driving you out of business. If you depend too much on other resources, eventually, when the prices of those resources change, your business model will have to change, very rapidly, or else you won’t stay in business.”

Why integrate livestock with crop production?

Speaking about why John and Amy decided to include animals from the onset, John says, “The primary reason we integrate livestock is to turn a liability into a resource.” For Frog Song, that means pigs are brought into sweet potato fields following harvests to help clean up

‘seconds’ and bits left behind that can otherwise harbor pests. In the warmth of the southeastern region where Frog Song is located, a sweet potato weevil thrives. The highly mobile bug can ruin inventories and crops in fields. Non-organic controls include herbicide applications to sweet potato fields following harvests, or soil fumigants. As an organic farm, Frog Song had to find other methods. “We decided pigs were the best way to plow over the land without using a lot of diesel. So the pigs will take sweet potato scraps and turn it into something that’s a very high-value product: organic bacon. Better than organic, it’s actually pasture-raised and on organic pasture!”

Another liability-turned-to-resource can be seen in the orchards. Chickens are ranged under established (2 years old or more) stone fruit trees after fruiting. As they scratch and peck around the trees, they effectively reduce plum curculio, millipedes, cutworms and other lepidoptera pests. To make the most of the benefits of the chickens’ manure, feed is concentrated around the base of fruit trees to maximize the time they spend scratching weeds and leaving behind manure.

Another liability-turned-to-resource can be seen in the orchards. Chickens are ranged under established (2 years old or more) stone fruit trees after fruiting. As they scratch and peck around the trees, they effectively reduce plum curculio, millipedes, cutworms and other lepidoptera pests. To make the most of the benefits of the chickens’ manure, feed is concentrated around the base of fruit trees to maximize the time they spend scratching weeds and leaving behind manure.

Cover crops and livestock integration

On farms with integrated systems of crops and livestock, cover crops can provide valuable forages. At Frog Song, cover crops are planted year-round, and almost always include a multi-species mix. From November to February, winter rye, coker oats, and wheat are planted. Buckwheat, 4 types of millet, and sorghum-Sudan grass go in from March to October. And from April through August, John plants Sunn Hemp as a stand-alone. All of these crops, in addition to certain cash crops like the sweet potatoes, are eventually grazed by animals.

Sunn Hemp is planted as a stand-alone cover crop in a pear orchard. “This would be a good time to graze it down by pigs, if you needed to. Sunn Hemp is kind of our backup plan for pig grazing. We try to have enough millet and sorghum and buckwheat after the sweet potato crop, and if we fail at any time, then we have acres and acres of the Sunn Hemp that would be a decent forage for them.” John recommends grazing sunn hemp only until about 20 inches tall. At about waist-high, it becomes too tough, high in a particular acid, and the pigs “just won’t eat it,” he says. Also of note: for grazing pigs in this area, the fence would be placed to exclude the pigs from the pear trees.

Sunn Hemp is planted as a stand-alone cover crop in a pear orchard. “This would be a good time to graze it down by pigs, if you needed to. Sunn Hemp is kind of our backup plan for pig grazing. We try to have enough millet and sorghum and buckwheat after the sweet potato crop, and if we fail at any time, then we have acres and acres of the Sunn Hemp that would be a decent forage for them.” John recommends grazing sunn hemp only until about 20 inches tall. At about waist-high, it becomes too tough, high in a particular acid, and the pigs “just won’t eat it,” he says. Also of note: for grazing pigs in this area, the fence would be placed to exclude the pigs from the pear trees.

The choice of which cover crops to plant for grazing centers around three questions for John. One, will the animals eat it, and at what stage is best to start grazing? Two, how much does it cost to establish, in both time and expenses, especially given that the cost of cover crop seeds can vary from year to year? And three, how does the crop fit in with the rotation? The answer to that third question, for Frog Song, has special implications for legume cover crops. Since one of Frog Song’s cash crops is legumes, they need at least 3 years in the rotations without legumes in order to avoid building up diseases like white rot. Sunn Hemp seems to be a distant enough relative that it remains in the cover-crop mix at Frog Song, and does not contribute to buildup of diseases affecting legume cash crops

The switch to on-farm breeding

For years at Frog Song, piglets were purchased off-farm, but after some time, John decided it was best to breed their own pigs on-farm. “After being in business for some years,” he explains, “sometimes the piglets aren’t there when you need them to be there, in your cycle.” Since beginning on-farm breeding with Red Wattle Hogs, the animals are bred and available at times that suit the farm, and the animals “stayed in good health and stayed productive.”

To maintain healthy genetics, a few sires from different lines are brought in to live on site. A few sows cycle through the “Honeymoon Suite” to breed with them, and then are introduced to farrowing pens, which are “good spots on the farm…basically giving the sow the best of what there is in that moment of the year,” with plenty of shade and quality forage. Within 7-14 days, the piglets have begun to graze the forage and are learning the cycles and systems of Frog Song.

“Certain animals can be pretty much addicted to grain,” John explained. “They won’t go forage for themselves, they’ll just wait for when the grain comes, then they get really nasty to have to battle out their siblings or bunkmates for that grain. In our system, we’re looking for the pigs who just want to go plow up any part of their block, go find their own sweet potatoes, and there’s really no way that a bully pig can dominate that system: they’ve all got plenty to eat, they’re stress-free, and by the time they get to the end of the block, there’s a new block waiting for them.”

Adaptations in infrastructure for livestock

Two of the most important pieces of infrastructure for livestock at Frog Song are electric fencing and animal housing. Training workers so that each understands how electricity flows through an entire fencing system has been key to being able to troubleshoot problems in the field quickly without slowing other parts of the operation down. And to keep a careful eye on the electric systems, John recommends having one person who is responsible for checking systems at least once a day. At Frog Song, handlers check the systems twice a day. Electric fencing is key to the paddock systems at the farm, typically set up as block-paddocks that are fractions of a longer, rectangle-shaped field. The animals move across the field into a new paddock every 5-7 days.

Two of the most important pieces of infrastructure for livestock at Frog Song are electric fencing and animal housing. Training workers so that each understands how electricity flows through an entire fencing system has been key to being able to troubleshoot problems in the field quickly without slowing other parts of the operation down. And to keep a careful eye on the electric systems, John recommends having one person who is responsible for checking systems at least once a day. At Frog Song, handlers check the systems twice a day. Electric fencing is key to the paddock systems at the farm, typically set up as block-paddocks that are fractions of a longer, rectangle-shaped field. The animals move across the field into a new paddock every 5-7 days.

For livestock housing, one important adaptation has to do with the clay soils at the farm: John has moved away from anything with wheels, such as chicken houses on trailers, because clay gets into tire seals, ruins them, and the seals need to be replaced often. New housing structures are custom-built using 2-inch metal tubing, in a design that can be picked up with a front-end loader and easily moved with a tractor.

Risks of raising animals and crops together

Understanding the risks of raising livestock is simple, but it is of the utmost importance. John explains, “How do you grow vegetables and raise animals at the same time? This is a really important part to talk about. This is where the farm can go really wrong if you don’t acknowledge your risks. But the risks are simple: you don’t want to get manure in the product in any way possible!”

The plans for dealing with this simple risk are taken seriously. In order to know where the risks lie, the farm identifies where manure is traveling, from paddocks to packing shed or plantings. These “Critical Control Points” (CCP’s) are part of the farm’s HACCP plan (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point Systems plan), which means they are “identified, verified, and validated” so they all get met. With animals moving around the farm often, John starts thinking about where the manure will go the moment he starts designing the layout of fields.

That means thinking about the flow of water. “I’d say, start there, as a farmer,” he suggests, “you need to look at ‘Which way does every drop flow?’ As it comes out of the sky and hits your farm. Then you need to know where your paddocks are, where you’re going to raise your crops, and what kind of crops you are going to raise (low or high risk).” Having staff trained in safe handling and protocols for visiting anywhere on the farm with manure or entering packing areas is also a necessary part of managing the CCP’s and risks of manure.

Benefits you can see: soil fertility

Despite the risks, workload, and infrastructure needs, having pigs and chickens is an integral part of what makes Frog Song successful. When asked about the benefits of the 12+ years of crop-livestock integration at the farm, John spoke about one key indicator of soil health: the health of the cover crops. In the first few years, some fields barely sustained a cover crop. Other fields with more clay had large incongruencies in growth over the area and in how water moved through them (areas with poor drainage and large puddles). Now these same fields produce uniform, lush patches of cover crops, and as John reflects on a decade-plus of integration, he says, matter-of-factly, “every year certain blocks are getting better.”

Fast-forward 12 years, and Frog Song Organics is a 62-acre operation with about 30 full-time employees and 20-40 acres in production at any one time. Located less than a 2 hour’s drive from several markets, Frog Song provides organic products year-round to four farmers markets and wholesale accounts in Gainesville, Orlando, St. Augustine, and Tampa, and through an online-order, customizable-box CSA program.

Fast-forward 12 years, and Frog Song Organics is a 62-acre operation with about 30 full-time employees and 20-40 acres in production at any one time. Located less than a 2 hour’s drive from several markets, Frog Song provides organic products year-round to four farmers markets and wholesale accounts in Gainesville, Orlando, St. Augustine, and Tampa, and through an online-order, customizable-box CSA program.  Another liability-turned-to-resource can be seen

Another liability-turned-to-resource can be seen

When John Bitter and his wife Amy started Frog Song Organics on 5 acres in 2011, a vision of how to carefully scale-up the farm was long in the works. They both had several years’ experience working with farms in the area, and each knew nearby markets well enough to know they had opportunities to grow. Looking ahead, they had also spoken with the owner of neighboring land about leasing additional acreage in the future.

When John Bitter and his wife Amy started Frog Song Organics on 5 acres in 2011, a vision of how to carefully scale-up the farm was long in the works. They both had several years’ experience working with farms in the area, and each knew nearby markets well enough to know they had opportunities to grow. Looking ahead, they had also spoken with the owner of neighboring land about leasing additional acreage in the future.

Hidden Hollow Farm has also seen improvements in soil health since integrating the livestock onto the cropping ground. “Soil organic matter has increased faster than any other model of farming that I know of,” Arlen said. “The soil health really hums.” As the cows leave patties on the fields, dung beetles burrow into the ground and distribute that manure, transporting nutrients down into the soil. Earthworm activity also increases the soil biology, and the pathways left behind by the dung beetles and the earthworms aid in water infiltration and retention.

Hidden Hollow Farm has also seen improvements in soil health since integrating the livestock onto the cropping ground. “Soil organic matter has increased faster than any other model of farming that I know of,” Arlen said. “The soil health really hums.” As the cows leave patties on the fields, dung beetles burrow into the ground and distribute that manure, transporting nutrients down into the soil. Earthworm activity also increases the soil biology, and the pathways left behind by the dung beetles and the earthworms aid in water infiltration and retention.

Mike runs and operates Shady Side Farm in Holland, Michigan. Along with help from his wife, Lona, their adult children, and Mike’s parents he farms on 150 contiguous acres, and an additional 20 acres that they rent nearby. He was one of the

Mike runs and operates Shady Side Farm in Holland, Michigan. Along with help from his wife, Lona, their adult children, and Mike’s parents he farms on 150 contiguous acres, and an additional 20 acres that they rent nearby. He was one of the  Mike has found that he learns a lot from observing the animals. “We ran sheep for a number of years,” he said. “And then all of a sudden we ran into an issue with parasites in the sheep.” There was a patch of milkweed in the pasture [a host plant for monarch caterpillars], and Mike noticed that when the sheep got to that spot they were stripping the plants of their leaves. “I had to ask the question,” Mike continued, “why were they doing that? Come to find out it was a way that they were paying attention to their bodies, and their bodies needed some way to have parasite control.” Milkweed contains a toxoid that can take out or reduce the parasite load in grazers and Mike realized that was the reason the sheep were so aggressively grazing the milkweed. “So I started looking at where I could find those same things in some planting mixes I could use for the lambs to graze on,” Mike said.

Mike has found that he learns a lot from observing the animals. “We ran sheep for a number of years,” he said. “And then all of a sudden we ran into an issue with parasites in the sheep.” There was a patch of milkweed in the pasture [a host plant for monarch caterpillars], and Mike noticed that when the sheep got to that spot they were stripping the plants of their leaves. “I had to ask the question,” Mike continued, “why were they doing that? Come to find out it was a way that they were paying attention to their bodies, and their bodies needed some way to have parasite control.” Milkweed contains a toxoid that can take out or reduce the parasite load in grazers and Mike realized that was the reason the sheep were so aggressively grazing the milkweed. “So I started looking at where I could find those same things in some planting mixes I could use for the lambs to graze on,” Mike said. place, and then you don’t implement it for a number of years. It takes time to settle into the brain.”

place, and then you don’t implement it for a number of years. It takes time to settle into the brain.”

With 20 acres in contiguous square blocks this gives Mike a perimeter fence that he can run electricity through. “We’ve got divider fences that can be hooked up with spring gates or string gates,” he said. “We can transfer power from the perimeter fence into an interior divide.” They use a variety of fencing for the cattle, sheep and lambs. The paddock systems get set up and moved on a daily basis throughout the summer, so that the animals are constantly moving around the farm.

With 20 acres in contiguous square blocks this gives Mike a perimeter fence that he can run electricity through. “We’ve got divider fences that can be hooked up with spring gates or string gates,” he said. “We can transfer power from the perimeter fence into an interior divide.” They use a variety of fencing for the cattle, sheep and lambs. The paddock systems get set up and moved on a daily basis throughout the summer, so that the animals are constantly moving around the farm.