Written by Brian Geier, OFRF Communications Manger. This article was originally published in the Spring 2025 Organic Broadcaster by Marbleseed.

In labs in Wisconsin and Indiana, researchers are studying how microbial communities found on different varieties of carrots might help lead to disease resistance on organic farms. At a field day in Illinois, ten varieties of carrots are served on paper plates to attendees, who taste and rate the sweetness, texture, and color. And on forty farms across the country, farmers try the new carrot varieties on-farm, via a decentralized trial service called Seedlinked. All are part of the “Carrot Improvement for Organic Agriculture” (CIOA) project, led by Dr. Phillipp Simon at the University of Wisconsin (UW) and partnered with the Organic Seed Alliance (OSA). The effort aims to develop and release new seed lines that can support a surging organic carrot industry that already represents 12% of the carrots grown in the US and is valued at over $120 million annually.

Advanced breeding lines of carrots are being evaluated at the Hoagland Lab at Purdue University, a partner on the CIOA project. To learn more, visit CIOA’s eOrganic page. Photo credit: Purdue University.

The CIOA is one of several projects developed and led in Wisconsin that are responding to the needs of various organic industries and doing critical work to empower farmers to elevate their operations. It serves as just one example of how the organic community in Wisconsin is leading the way toward new innovations through research, helping to advance organics nationwide.

Organics in Wisconsin

Wisconsin is undoubtedly a leader in organic farming. It ranks 5th in the nation in terms of organic market value, after having grown 16% in just two years to $312 million in 2021. The state has the highest number of organic farms of any state outside California, with 1,455 certified operations, representing 8% of the nation’s total. And, Wisconsin is the nation’s leader in the number of organic farmers statewide in several commodities: field crops, livestock and poultry, layer chicken farms, and pig farms.

By many indicators, the growth trend for organic in Wisconsin is poised to continue: the state ranks second in the number of non-certified farms with transitioning organic acres, an indicator of the potential for growth in a state’s organic sector. And according to UW, the majority of organic farmers in the state (80%) plan to maintain or increase their organic production.

Federally-Funded Research in Wisconsin

To begin a discussion on Federal funding, it can be useful to decode some alphabet soup. Organic research funding reaches Wisconsin through the USDA’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) via the Organic Research and Extension Initiative (OREI), the Organic Transitions Program (ORG), and the Agricultural Research Service (ARS). Project leads are often researchers at universities, but many projects involve collaborative teams of researchers in other states, and many have organic farmers collaborating in research as well.

Project leads often have ongoing connections to organic farmers, and ideas for research can come from a variety of places including formal surveys or simply through discussions with growers. According to the 2022 National Organic Research Agenda, a comprehensive survey of organic producers across the country conducted by the Organic Farming Research Foundation (OFRF), organic farmers in the Great Lakes ag-ecoregion have identified three key research concerns:

- Climate adaptation and resilience.

- Weed, pest, and disease management.

- Soil health.

NIFA has awarded over $19 million in grants to the state’s research institutions for organic research to address these and other concerns. These grants translate to over $380 million in economic activity, since every dollar invested in agricultural research generates about $20 in benefits, according to a long-term study by the USDA’s Economic Research Service (ERS). UW has played a crucial role, securing and investing $8 million of those grants. The ARS has historically funded 20 projects in the state researching organic topics, but currently, only two of those remain active, revealing a gap in the institution’s portfolio.

Innovative Projects Ongoing in Wisconsin

Research led by Dr. Yang, left, seen here standing in his lab alongside business collaborator Daniel Burgin, is bringing new biological agents to organic growers that can help protect apple, tree, and citrus trees from disease. Photo credit: UW.

Organic research underway in Wisconsin serves a diverse range of production systems, from vegetables to tree fruits and dairy.

Besides the CIOA, which is funded through OREI, another project at UW-Madison, led by Dr. Rebecca Larson and funded by ORG, is partnering with organic dairy farmers through the Organic Valley Cooperative. The team is developing life-cycle analysis models for eight dairy-producing regions so farmers can measure and meet conservation goals. Also funded by ORG but headquartered at UW-Milwaukee, a project led by Dr. Ching-Hong Yang is working to boost the efficacy of a bacterial strain in controlling fire blight in organic apple and pear trees. Dr. Yang, along with a business partner and researchers at the University of Florida, is also testing the same strain for efficacy in lessening the severity of citrus greening.

Wisconsin’s organic producers have a diverse range of operations, and the challenges that organic farmers face are varied. Researchers are answering the calls with strong collaborations, multi-state networks, and dissemination components to bring key findings that farmers can use to inform decisions on their operations.

Resources and Insights from Research Completed in Wisconsin

The Organic Alternatives to Conventional Celery Powder project, led by Dr. Erin Silva at UW, addressed a constraint of the organic processed meat industry. This was a timely project, as the National Organic Program (NOP) was about to sunset the allowance of non-organic celery powder. But the question remained: can organic systems produce celery powder with the nitrate content needed for curing meat? The project verified that organic production systems can produce celery powder with sufficient N content for the industry.

Another project, called Connecting Community to Strengthen Organic Seed Breeding and Research and led by the OSA, responded to an urgent need to recruit and train a new generation of plant breeders specializing in cultivar development for organic systems. Plant breeders whose methods comply with organic standards have become an endangered species. The needs of organic seed farmers were collected and presented in OSA’s 2022 State of Organic Seed Report. And yes, 2022 is the same year as OFRF’s NORA report mentioned above. In fact, OFRF and OSA collaborated on an OREI-funded project to conduct the surveys and produce both reports!

Another project, called Connecting Community to Strengthen Organic Seed Breeding and Research and led by the OSA, responded to an urgent need to recruit and train a new generation of plant breeders specializing in cultivar development for organic systems. Plant breeders whose methods comply with organic standards have become an endangered species. The needs of organic seed farmers were collected and presented in OSA’s 2022 State of Organic Seed Report. And yes, 2022 is the same year as OFRF’s NORA report mentioned above. In fact, OFRF and OSA collaborated on an OREI-funded project to conduct the surveys and produce both reports!

OSA’s seed-breeding project conducted the Student Organic Seed Symposium (SOSS), an annual networking and professional development opportunity for graduate students in plant breeding and seed production for organic systems. The symposium was held at West Virginia University to convene a greater geographical and ethnic diversity of students. A speed-mentoring activity amongst participants was found to be especially valuable in identifying the next steps in their professional development. Reflecting on the Symposium, one seed-breeder-in-training stated: “It takes all of us (farmers, researchers, chefs, storytellers) to further our aims of creating genetic diversity and adapting to climate change.”

While research projects in Wisconsin may have been born from the challenges that Wisconsin’s organic farmers face, the knowledge and resources created by projects in the state have made significant contributions to the broader organic community.

Advocacy to Protect Federal Funding for Organic

Certified organic produce now makes up more than 15% of total produce sales in the United States. Organic dairy and eggs now constitute more than 11% of the total market. And overall, organic sales have doubled over the last 10 years and in 2024 made up about 6% of the total US food market. By most measurements, organic food is trending upward nationally, not just in Wisconsin. Most notably, the growth of organic sales is consistently outpacing the growth of the overall food market. To say it another way, we might be heading into a future that is more and more organic!

But will we get there?

Despite the growth of the organic sector, organic agriculture research funding makes up less than 2% of the total research budget at the USDA, and less than 1% of the Agricultural Research Service’s (ARS) budget. Additionally, much of the research focused on conventional agriculture relates to chemical applications or genetic traits—technologies that organic producers do not, and if certified, can not, use. To put it another way, organic research benefits all farmers, including conventional ones, but not the other way around.

In order to sustain the growth in organic acreage, producers, and products, it is crucial that more USDA funding be organic and applicable to all farmers. National policy priorities identified by OFRF include:

- Increasing USDA’s research funding for organic research through both competitive grant programs at the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) and intramural research at ARS to reflect its market share and growth trajectory.

- Fully funding the Organic Data Initiative to provide the necessary market analysis of an increasingly sophisticating sector.

- Expanding the accessibility and applicability of technical and financial assistance programs for organic farmers.

At the time of this article’s writing (early 2025), uncertainty abounds within the organic community as federal funds for a number of programs related to organic farming, addressing climate change or support for specific farming communities ,are currently inaccessible due to executive action by the new administration in January. A federal judge recently ruled against the, but congressionally appropriated funds for active, ongoing organic research, conservation practices, and other services that organic farmers and researchers rely on remain inaccessible. This is causing immense uncertainty and disruption.

The moment calls for steadfast advocacy and a commitment to organic research programs. OFRF offers resources and ways to get involved: join OFRF’s newsletter to stay informed, share your story if you are a farmer or researcher impacted by interruptions or resumptions of Federal funding, and visit OFRF’s advocacy page to learn more.

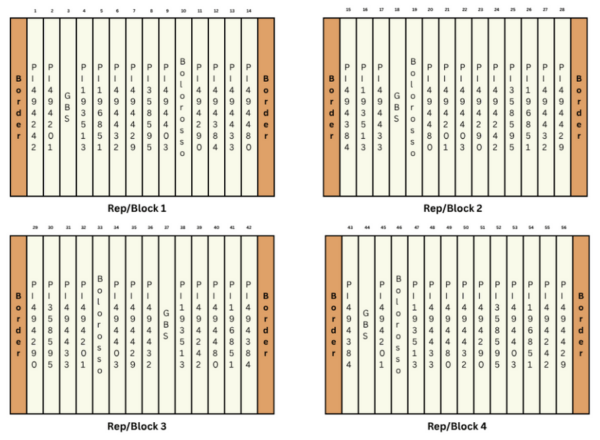

The plot layout includes 12 accessions from a western regional station, all of Ethiopian origin, alongside two commercially available varieties:

The plot layout includes 12 accessions from a western regional station, all of Ethiopian origin, alongside two commercially available varieties:

The project builds on a previous OREI grant that helped to identify varieties that worked well in organic crop rotations with sorghum. These varieties are now being evaluated to identify those with higher protein and sugar content, and better protein quality (measured both by digestibility and consumer preference). Dr. Thavarajah calls her approach “participatory breeding” that includes both consumers and farmers in the process. Interestingly,

The project builds on a previous OREI grant that helped to identify varieties that worked well in organic crop rotations with sorghum. These varieties are now being evaluated to identify those with higher protein and sugar content, and better protein quality (measured both by digestibility and consumer preference). Dr. Thavarajah calls her approach “participatory breeding” that includes both consumers and farmers in the process. Interestingly,