Farmer-Led Trials Program Spotlight: Passion Garden

Experimenting with on-farm materials to create organic soil amendments

Written by Mary Hathaway, OFRF’s Research & Education Program Manager, and Kay Bell, FLT Program participant

Mesquite bean pods, collected by Kay Bell, to use as a soil amendment at Passion Garden

Kay Bell has been farming for ten years on her three-acre farm in Waco, TX, called Passion Garden. She grows a variety of fruits, vegetables and herbs that she sells as fresh produce and herbal teas at local farmers markets and health food stores. Her farm is currently in the process of transitioning to certified organic, with a focus on building her own on-farm fertility.

Kay has a big focus on using locally available, on farm inputs to help improve her soil health, and has long considered using the pods of the Mesquite Tree Bean in her fertility plan. As a farmer focused on growing the health of her community, she looked into the nutrient content of Mesquite Bean, and realized that it has a high protein content and is rich in many nutrients. Since the tree is prevalent on her property, and the pods are not too difficult to harvest, she believed it could be a useful amendment in building her soil health.

Using Mesquite Beans as a Soil Amendment for Tomatoes

To test her idea, Kay wanted to build an experiment that would assess the impact of mesquite bean meal as a soil amendment on the yield of ‘Celebrity’ tomatoes, one of her favorite tomato varieties. She hopes that the addition of Mesquite Bean Meal (MBM) will result in a measurable increase in total or marketable tomato yield compared to her normal soil amendments in raised beds. To create the MBM, Kay harvested the pods, and used a simple mill to grind them so that they were in an easy to use powder format.

On-Farm Trial Plan

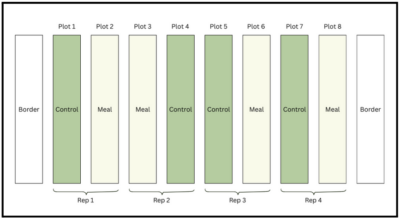

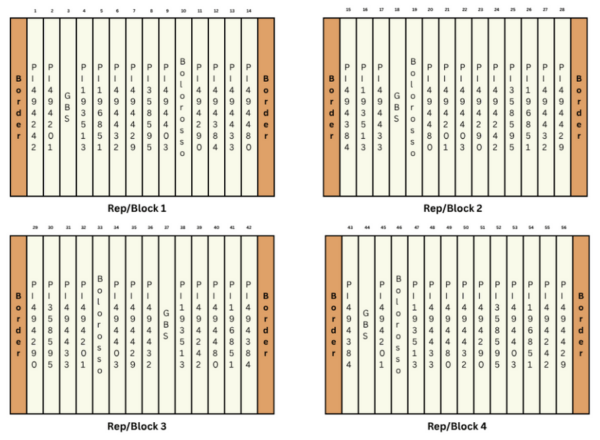

Plot map from Passion Garden’s FLT Program trial

In the beginning of August 2025, with technical support from OFRF’s Farmer-Led Trials Program staff, Kay prepared eight raised beds, each measuring 4 feet wide by 8 feet long, to provide a uniform growing area for the plants. All of the beds were filled with the same base soil mixture and compost. Kay planted 4 tomato plants in each of the beds in September. At the time of transplanting, the four treatment raised beds received ½ cup of the MBM. During the growing season, all of the beds were treated consistently, with the same irrigation schedule, staking, and pest management.

By mid-October, Kay began tracking the yields, her key metric of the trial. This was recorded as total weight and marketable weight, the weight of tomatoes that meet standards for commercial sale (free from major blemishes, cracks, or rot). Kay also took observations of plant health, pest pressure, and any plant losses that might impact the findings for the trial.

Farmer-Led Trial Results: Tomato Production Increased with On-Farm Amendment

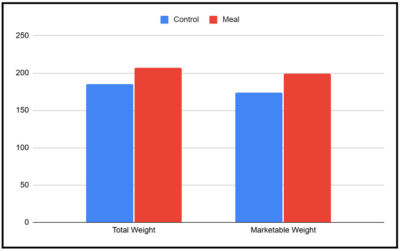

Once all of Kay’s data had been collected, the analysis revealed a significant difference in yield between the control and meal treatments, with the treatment receiving the MBM yielding more per plant and overall than the control treatment.

Anecdotally, Kay observed improved water drainage and thinks that the MBM helped improve the drainage in her clay soils. She also noted increased presence of worms and other soil organisms, and she speculates that the natural sugars in the MBM help attract more soil invertebrates.

Yield results from Passion Garden’s FLT Program trial, showing yield of tomatoes in the control group (blue) vs the group grown using Mesquite Bean Meal (red).

Kay is very motivated by the success of this trial and plans to use MBM as a pre-transplant amendment throughout her farm. She is also excited to spread the word on the many uses of Mesquite Bean – including as a coffee alternative, as a gluten free flour in baking, and a sweet jelly.

Stay tuned for a final report on Kay’s trial coming out later this year.

Prepped beds at Passion Garden during the 2025 FLT.

“I know this trial has made me stronger as a farmer. And I just look forward to experimenting with nature to grow things with resources I have on-farm.”

– Kay Bell, FLT Program Participant

Tomatoes harvest from Passion Garden, during the 2025 trial.

This is part of a series of blogs highlighting farmers who are participating in OFRF’s Farmer-Led Trials program. Farmers receive technical support to address their production challenges through structured on-farm trials. To learn more about OFRF’s Farmer-Led Trials Program, visit our website page at https://ofrf.org/research/farmer-led-research-trials/

To learn more about Kay Bell and Passion Garden, check out this ATTRA article.

Kay is President of the National Women in Agriculture Association Texas Chapter: https://www.nwiaa.org/texas

Rachel was motivated to implement conservation practices to reduce the risks associated with irrigation costs, one of the biggest concerns on her farm. During the very hot Arizona summers, Rachel can spend up to four hours a day hand-watering her crops. Not only is this time-consuming, but because she operates an urban farm that’s reliant on city water, it can be expensive. She is also passionate about

Rachel was motivated to implement conservation practices to reduce the risks associated with irrigation costs, one of the biggest concerns on her farm. During the very hot Arizona summers, Rachel can spend up to four hours a day hand-watering her crops. Not only is this time-consuming, but because she operates an urban farm that’s reliant on city water, it can be expensive. She is also passionate about  At Little Lighthouse Farm, soil health was restored because of the years of research on the benefits of cover cropping. Better soil health allows Rachel to grow better crops, which provide nutritious products to community members. Research funding makes this all possible and demonstrates that innovations in organic agriculture research can result in widespread adoption of beneficial practices, helping farms of all sizes and production types meet conservation goals. And the benefits of research extend beyond the farm, too. According to an analysis done by the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS), every $1 invested into agricultural research triggers a

At Little Lighthouse Farm, soil health was restored because of the years of research on the benefits of cover cropping. Better soil health allows Rachel to grow better crops, which provide nutritious products to community members. Research funding makes this all possible and demonstrates that innovations in organic agriculture research can result in widespread adoption of beneficial practices, helping farms of all sizes and production types meet conservation goals. And the benefits of research extend beyond the farm, too. According to an analysis done by the USDA Economic Research Service (ERS), every $1 invested into agricultural research triggers a

Samantha Otto is the founder and farmer of The Woven Trifecta, a 10-acre farm in western Michigan. Currently in transition to organic, the farm focuses on diversified vegetables for a CSA, local farmers market, as well as farm-to-school sales throughout the school year. Samantha raises Jacob sheep for fiber as well as assorted poultry for meat and eggs. The livestock is rotationally grazed on just over 3 acres of pasture, with 2 acres of no-till beds in production.

Samantha Otto is the founder and farmer of The Woven Trifecta, a 10-acre farm in western Michigan. Currently in transition to organic, the farm focuses on diversified vegetables for a CSA, local farmers market, as well as farm-to-school sales throughout the school year. Samantha raises Jacob sheep for fiber as well as assorted poultry for meat and eggs. The livestock is rotationally grazed on just over 3 acres of pasture, with 2 acres of no-till beds in production.

The plot layout includes 12 accessions from a western regional station, all of Ethiopian origin, alongside two commercially available varieties:

The plot layout includes 12 accessions from a western regional station, all of Ethiopian origin, alongside two commercially available varieties:

Farmacea’s project is a strawberry trial comparing traditional plastic mulch to a living mulch of white Dutch clover. Their research question is simple but will help Farmacea determine which

Farmacea’s project is a strawberry trial comparing traditional plastic mulch to a living mulch of white Dutch clover. Their research question is simple but will help Farmacea determine which