An Organic Approach to Increasing Resilience

Few farmers need official reports to tell them that “increasing weather volatility” and climate change threaten their livelihoods and the resilience of their farming and ranching operations. With historic droughts, wildfires, flooding, and hurricanes in recent years, more farms are facing variable yields, crop losses, increased weed, pest, and disease pressures, and intensifying soil degradation, erosion, and compaction.

By utilizing organic and sustainable practices to build soil health, farmers and ranchers can improve their resilience and reduce risk as our climate changes. While practices can vary depending on your operation, establishing optimum soil organic matter (SOM) and biological

activity will help your operation through the difficult times to come.

Crop-Livestock Integration Panel with Organic Farmers

Are you an organic farmer that is interested in using your livestock in your crop rotation? Are you wondering how others have overcome some of the complexities of integrating your farm system? Would you like to hear directly from farmers who have experience in this topic? If so, then this webinar is for you.

This Seeds of Success farmer-to-farmer networking session was an engaging opportunity where farmers came together to ask questions and share their lived experience in integrating crops and livestock in their production systems.

This session features three farmers that have built resilience and a dynamic organic system:

- Ben Coerper, Wild Harmony Farm

- Tomia MacQueen, Wildflower Farm

- Raymond Hain, recently retired from Grain Place Foundation

OFRF has partnered with the Organic Farmers Association (OFA) and National Organic Coalition (NOC) to lead a series of virtual farmer-to-farmer networking sessions. These facilitated events will be engaging opportunities for farmers to share their challenges and successes, and will be accompanied with relevant resources you can use.

Funding for this series is provided by a cooperative agreement between OFRF and USDA- NIFA to highlight research investments made through both OREI and ORG grant programs.

Infrastructure and Crop-Livestock Integration

In OFRF’s 2022 National Organic Research Agenda (NORA), organic farmers and ranchers across North America shared a common concern about the lack of technical assistance and educational resources available for Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems (ICLS). Integrating crops and livestock results in numerous benefits, however the process can also lead to increased complexity, especially for farmers who must adhere to National Organic Program rules and regulations.

This series of resources focused on Crop-Livestock Integration is informed by interviews with four highly-experienced organic producers that shared their challenges, successes, and advice for others interested in integrating livestock and crops on their organic farms.

Infrastructure for integrating animal and crop systems includes animal housing, watering systems, and fencing. Learn how farmers develop infrastructure that match the type and age of animal, are highly movable, and are adapted to soil and climate conditions.

What’s Happening with Organic Farming Research in Pennsylvania

Written by Brian Geier, OFRF Communications Manger. This article was originally published in Pennsylvania Certified Organic’s (PCO) Organic Matters publication. See the article in PCO’s Winter/Spring 2025 edition.

Before diving into the importance and impact of organic research in Pennsylvania, let’s start with some national context. Nationwide, certified organic produce now makes up more than 15% of total produce sales in the United States. Organic dairy and eggs now constitute more than 11% of the total market. And overall, organic sales have doubled over the last 10 years and in 2024 made up about 6% of the total US food market. By most measurements, organic food is trending upward. Most notably, the growth of organic sales is consistently outpacing the growth of the overall food market. To say it another way, we might be heading into a future that is more and more organic!

But will we get there?

Despite the growth of the organic sector, organic agriculture research funding makes up less than 2% of the total research at the USDA, and less than 1% at the Agricultural Research Service (ARS). Additionally, much of the research focused on conventional agriculture relates to chemical applications or genetic traits—technologies that organic producers do not, and if certified, can not, use. To put it another way, organic research benefits all farmers, including conventional ones, but not the other way around.

In order to sustain the growth in organic acreage, producers, and products, it is crucial that more USDA funding be organic and applicable to all farmers. National policy priorities identified by the Organic Farming Research Foundation (OFRF) include:

- Increasing USDA’s research funding for organic research through both competitive grant programs at the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) and intramural research at ARS to reflect its market share and growth trajectory.

- Fully funding the Organic Data Initiative to provide the necessary market analysis of a rapidly sophisticating sector.

- Expanding the accessibility and applicability of technical and financial assistance programs for organic farmers.

To learn more about this policy work that supports organic nationwide and in Pennsylvania, visit OFRF’s advocacy page.

Organic Research in the Keystone State

Pennsylvania is a powerhouse of organic agriculture. It ranked 4th in the nation with over 100,000 certified acres and 1,200+ farms generating $1 billion in sales in 2021, according to the latest organic survey by the National Agricultural Statistics Service.

The USDA’s NIFA has awarded over $28 million in grants to the state’s research institutions for organic research. Penn State University has played a crucial role, investing $12 million. The ARS has historically funded 17 projects in the state researching organic topics, but currently has no active projects.

Organic farmers in the state and region have identified three key research concerns (according to the 2022 National Organic Research Agenda):

- Climate adaptation and resilience.

- Pest management.

- Soil health.

Active Research Projects in Pennsylvania

Recent NIFA investments, through programs like the Organic Research and Extension Initiative (OREI) and the Organic Transitions Program (ORG), have provided nearly $12 million over the past four years to ongoing projects with an organic focus in Pennsylvania. Key projects at Penn State focus on intensifying production and improving resilience of organic grains, developing a nitrogen decision support tool, testing anaerobic soil disinfection (ASD) in fields and in high tunnels, tracking foraging patterns of organic bees, evaluating perennial crop rotations, and developing parasite resistance in dairy cattle. Another project looking at immersive experiential education of urban educators is underway at Drexel University.

OFRF’s State-By-State leave-behinds provide data on the organic industry and organic research in states, and can be used to help farmers, researchers, and advocates when articulating needs for proposals or advocating for policy.

Source: Penn State Weed Science

Source: Penn State Weed ScienceOREI-funded research on organic grain production (led by Dr. John Wallace) builds on previous research on reduced and no-til strategies, including planting into high-residue cover crops. Credit: Penn State Weed Science.

Besides providing new knowledge to organic growers, each of these research projects have other direct and indirect benefits worth noting. The Economic Research Service estimates that every $1 spent on agricultural research generates an additional $20 in benefits to the economy. In Pennsylvania, that means the $28 million for organic research translates to $560 million in economic activity. This effect can be seen given the growth of the value in Pennsylvania’s organic production between 2019 and 2021. In 2019, Pennsylvania had 1,039 organic farms with over $740 million in farmgate sales. In 2021, those numbers grew to 1,123 organic farms generating over $1 billion. Research provides real economic opportunities to farms looking to maximize both their economic return and their ecological impact.

Additionally, organic research provides professional training opportunities for undergraduates, graduates, and postdoctoral fellows on organic systems, and promotes symbiosis between up-and-coming researchers and the organic community. As Dr. Ajay Nair, newly appointed as the Department of Horticulture Chair at Iowa State University explained in a recent interview with OFRF, OREI “is the foundation for several of the organic projects that happen across the country. It serves as a good platform for us to reach out to organic growers and for organic growers to reach out to us and say, ‘Hey, can we address this particular issue that is coming up?’ These OREI grants,” he explains, are “actually helping to build our network…to help us build teams across the country.”

How Pennsylvania Research Benefits Growers Across the Eastern US

Just as organic research can be applicable to all farmers, multi-state projects led in Pennsylvania are bringing new findings to organic farmers facing similar challenges across regions. For example, the OREI-funded project assessing ASD in field, led by Dr. Gioia at Penn State, includes similar research plots led by Dr. Xin Zhao at University of Florida. Results from Pennsylvania may provide insights for growers in the Northeast who face challenges managing soil borne diseases, while the plots in Florida reflect conditions faced by organic growers in the Southeast, but results from each region might inform growers who face similar challenges to similar cropping systems. Growers interested in managing soil health with ASD in the Upper Midwest or the Southeast might find the eOrganic webinar from Dr. Zhao valuable. The webinar focuses on selecting the right carbon source for the organic practice of ASD, which includes insights from the trials on Pennsylvania farms. All growers who want to use ASD to support their transition period to organic farming may be interested in the additional grant awarded to Dr. Gioia and his team to assess the economic viability of using ASD during the transition to organic to control pests and weeds. Additionally, any grower using or considering using ASD can share their story and contribute to the project. “The survey,” Dr. Gioia explains “is part of the bottom-up approach our team have been using to improve the ASD application method and make sure that our research is relevant to growers and meets their needs.”

Source: Francesco Di Gioia/Penn State

Source: Francesco Di Gioia/Penn StateResearch at Penn State evaluates the impacts of cover crop residues combined or not with wheat bran and molasses as a carbon source for ASD applications on lettuce. The project supports similar research being conducted at the University of Florida. Credit: Francesco Di Gioia/Penn State.

Completed Projects Provide New Resources for Organic Growers

Aside from the active projects above, several NIFA-funded organic research projects have been completed in Pennsylvania. While they may be concluded, the benefits of these organic projects continue. The results of these studies are not limited to publication in academic scientific journals or relevant only to scientists. Researchers, farmers, and extension specialists often collaborate to share the results of studies in ways that are meaningful and applicable to farmers.

Take soil microbial management, for example. An OREI-funded study led by Dr. Jason Kaye at Penn State involved adding different sources of microbes (composts, forest soils, and other sources) to soils and measuring microbial populations. The project partnered with Pasa Sustainable Agriculture to collaborate with working farmers to conduct studies on working farms. While measurements of soil microbes may not be enough to provide specific recommendations to growers, the knowledge of how microbe populations change under management conditions and how they interact with plant crops can help farmers make better decisions.

Assuming soil microbes are fascinating to everyone with an interest in organic matters, let’s digress here for a moment. There are a myriad of ways that microbes can help or hinder organic systems: Microbes called biostimulants can release hormones into the soil that can help increase plant growth, while others can degrade the stress chemicals that plants produce during drought, helping plants become more resilient. Some microbes called biofertilizers can unlock nutrients in soils that plants cannot access themselves, helping where there may be excess nutrients, while other biofertilizers exchange nutrients directly with the plants in exchange for carbon. And get this—some perform better than others. That is, some biofertilizers that exchange phosphorus for carbon, called arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), offer plants more phosphorus in exchange for the same amount of carbon when compared with other AMFs.

When research-generated insights like these are made available and then accessed, farmers can make better-informed decisions for years to come. All of this fascinating information and more is available to farmers on eOrganic (see Management of Soil Microbes on Organic Farms and Soil Microbes in Organic Cropping Systems 101). Launched in 2009, eOrganic is a national, internet-based, interactive, user-driven, organic agriculture information system for farmers and agricultural professionals.

Want To keep Up With Organic Research in Your State or Nationally?

Aside from using eOrganic, growers and researchers can look forward to a new Organic Content Hub being developed by the OFRF, coming in early 2025. The Content Hub will be searchable by topic, crop, and region, and will provide users with the most current research relevant to organic farming. (Follow OFRF on social media and sign up for our newsletter to get updates on the Content Hub, organic research updates, new organic resources, and more.)

A figure developed by a graduate student (Laura Kaminsky) working on an OREI-funded project during 2019-23 at Penn State, illustrates examples of beneficial microbes. The left diagram shows nitrogen-fixing bacteria, housed either in nodules on legume roots or free-living in the soil. The right diagram illustrates arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) (pink) associated with plant roots. See Soil Microbes in Organic Cropping Systems 101.

Moving Forward With Organic Research

Organic farming research is generating economic activity in Pennsylvania, providing professional development to researchers and students across the east, forming regional networks between researchers and growers, and producing publications being used by organic growers across the country. One might say that the current state of research in Pennsylvania is healthy and humming!

Looking to the future, it is critical that federal funding keeps up with the growth of the organic movement nationally and in the state. OFRF and partners work daily to bolster and protect this funding, and we are always looking for farmer and researcher partners in this work. If you are an organic farmer or researcher and are willing to share your story, your experiences can be some of the best fodder for advocating for or directing future organic research in Pennsylvania.

Planting for Resilience

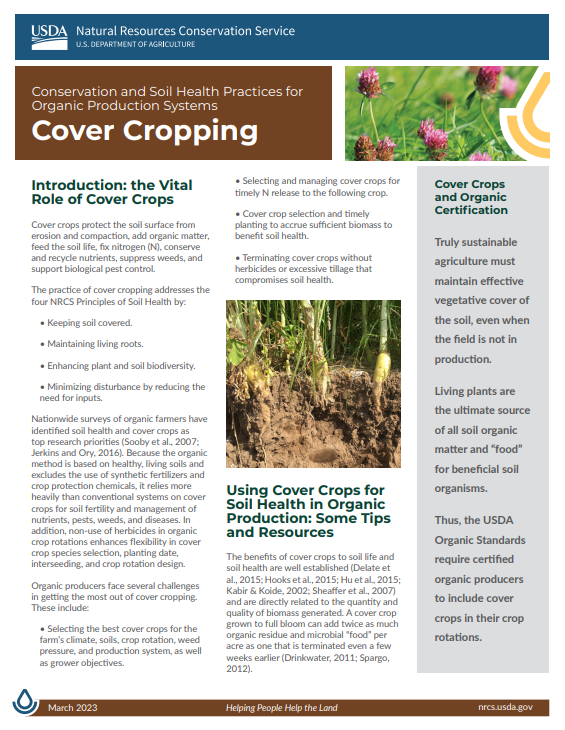

Reflections on Cover Crops and the Vital Role They Play in Organic Farming

By April Thatcher, farmer at April Joy Farm and OFRF Board President

Cover Crop Seed at AJF | Oats, radish, vetch, barley, and red clover.

Cover crops are a central part of balance on my Southwest Washington farm. In fact, they’re a vital tool in organic systems across the United States, helping to regenerate the soil, suppress weeds, and build resilience in the face of a changing climate. And yet, I’ll admit, for all their benefits, cover crops have been a source of some head-scratching moments for me over the years.

When I first started using cover crops, I had a lot of questions—many of the same ones I still hear from other new growers today.

- What mix of plants will work best with my soil type, climate, and crop needs?

- How do I know my cover crops are adding value to my system?

- What type of equipment do I need to manage cover crops successfully?

- And perhaps the most common question I get from fellow farmers is: How do I transition from a lush, green cover crop to a seedbed ready for planting without disturbing the soil too much?

Organic farming is a relationship between the land and the farmer, and I think of cover cropping as one big, ongoing conversation in this relationship. It’s a journey of experimentation, observation, learning, and refining techniques year after year. Each piece of land, each crop, and each season calls for a different approach, and what works for one farmer might not work for another.

On my farm, I’ve spent years experimenting with different cover crop mixes and timing strategies. I currently use a mix of cover crops—grasses, legumes, and broadleafs—depending on what I observe the soil needs. Legumes like peas and clover can add nitrogen to the soil, while deep-rooted crops like daikon radishes help break up compacted layers and improve soil structure. The key for me is to support functional diversity—both above and below the ground.

The Role of Cover Crops in a Living Soil System

When we treat soil as simply a medium to grow crops, we miss out on the extraordinary potential it has to regenerate life, sequester carbon, improve the nutritional value of our food, reduce off farm inputs, and to act as a buffer against the many challenges we face today.

Cover crops are a powerful tool to help unlock this potential. These crops are not meant to be harvested but rather are grown specifically to feed the soil. When used strategically, cover crops can help reduce soil erosion, capture and recycle nutrients, promote nitrogen fixation, increase organic matter, suppress weeds, and even manage pests—all while nurturing the living, complex web of life in our soils.

Cover crops are a critical tool in the organic farmer’s tool box to help build resilience on the ground—not just in the soil but in our entire farm ecosystem. And that resilience is more important now than ever as climate change presents erratic new challenges to farmers across the country.

Lessons from the Field: Cover Cropping in Practice

Cover Crop Kale | Sometimes, we don’t mow or turn under our market crops after we’ve finished harvesting. We underseed cover crops directly into these fields because, like cover crops, these plants continue to provide benefits for our system. Case in point- this tree frog has it made in the shade. Photo credit: Lauren Ruhe

I’ve learned over the years that there is no one “right” way to utilize cover crops. I’ve surrendered to the reality that on highly diversified operations like mine, cover cropping is always going to be a process of experimentation, observation, and refinement. What works one year might not work exactly the same the next, and that’s okay. If we are observant and committed to keeping records of our trials, we can glean important knowledge every season of the year. The goal isn’t perfection; it’s progress.

After eighteen years of working with cover crops on my 24 acre farm, here’s a bit of what I have gleaned – what I would tell my new-farmer-self if I could:

- Start simple and make small adjustments to your basic cover crop plan year over year. When I first started utilizing cover crops I was overly enthusiastic. Every year I’d try a bunch of different, complex seed mixes to try and find the perfect one. That was a mistake. I wish I’d stuck with a simple mix of two or three species (grass/legume/broadleaf) for the first few years. If I had done so, and made small refinements year over year, (adjust seeding rates, sowing dates, etc.) it would have saved me time in the long run. Instead of changing way too many variables every year, I would have built up a steady, reliable mix customized to my system faster- one that incrementally added stacking benefits to my system year over year.

- Pick only one (or two at most) goals. I had so many needs when I started using cover crops. I had soil compaction, low nitrogen, low organic matter levels, and erosion and leaching to worry about. But starting out, I would have been better off picking just one of these to focus on addressing through the use of cover crops instead of trying to solve all of them at once. Over time, you can build on your success. But aim for the small wins, having faith they will add up over time.

- Be mindful of your equipment and resource limits. We have hot, dry summers at my farm. So interestingly, irrigation is a big challenge for me in terms of using summer cover crop crops. Same goes for sowing fall cover crops, which I want to sow as early as I can to maximize nitrogen fixation. Even though I have the equipment to sow, cultipack and terminate them successfully, if I can’t get them to germinate without water I’m at square one. If you don’t have equipment to crimp/roll cover crops or don’t have a flail mower, make sure to be strategic about the species in your mix. Have a plan for seeding, and have a plan for terminating your cover crops that is practical for your operation.

- Nest your cover crops into your overall crop system. Your cover cropping plan has to work within the larger context of your farm plan. Part of this means being realistic about the resources (including labor) necessary to implement your cover crop strategy (see bullet point above). Part of this means being diligent about planning your cover cropping efforts as diligently as you do crops for your market. It’s all too easy in the heat of the season to bail on your cover cropping plan because some of the details aren’t quite worked out or you didn’t order seed, etc. Be intentional about making sure your cover crop system compliments versus competes with your market crop system. At my farm, tasks for cover crop soil prep, sowing, management, monitoring, and termination tasks are all included in my annual farm plan schedule. I don’t have to think about organizing or planning anything cover crop related once the season gets started; I can focus simply on implementation.

Every farmer who wishes to utilize cover crops successfully has specific soil health needs, goals unique to their operation, and different equipment and time constraints. So while there’s no single, universally right approach to cover cropping, we can all benefit from taking a strategic approach to working with cover crops.

Summer Cover Crop Mix | A favorite combination for warm weather. Oats, Buckwheat, Poppies and Phacelia.

Bridging Experience with Research: OFRF’s New Guide to Cover Cropping

That’s why I’m so excited to share a valuable new resource for farmers: a comprehensive organic cover cropping guide developed through OFRF’s ongoing partnership with the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). This guide is designed to help farmers—whether they’re just starting out with cover crops or refining their strategies.

What makes this guide so valuable is that it’s grounded in both science and experience. It combines years of research on the benefits of cover cropping with practical, field-tested strategies from organic farmers like myself. It provides an overview of the steps for selecting cover crops, managing them through the growing season, and terminating them in a way that benefits both the soil and the farmer’s bottom line. And it offers a collection of other regionally specific resources for farmers to dive in deeper. You can also find more in depth information in OFRF’s Soil Health and Organic Farming guide to Cover Crop Selection and Management.

Whether you’re looking to improve your soil’s health, reduce off-farm inputs, support pollinators, or make your farm more resilient to climate change, cover crops can be a powerful tool in your toolkit. This guide is full of practical, research-based advice to help farmers make informed decisions about how to integrate cover crops into their systems.

Organic Researcher Spotlight: Dr. Dil Thavarajah

A breeding pipeline is developing improved pulse crops for organic farmers in the southeast

Written by Brian Geier

New cultivars of pulse crops (lentils, chickpeas, and field peas) may soon be available to organic farmers! These improved varieties, under development through a project led at Clemson University (CU), will:

- be suitable for crop rotations with cash crops currently being grown on organic farms in North and South Carolina,

- have high protein content and quality, and

- be climate resilient (to heat, drought, and cold stress).

The Principal Investigator on the project, Dr. Dil Thavarajah, is an internationally-recognized leader in pulse biofortification (breeding for nutritional traits) who leads CU’s Pulse Biofortification and Nutritional Breeding Program. Her project, Sustainable, high-quality organic pulse proteins: organic breeding pipeline for alternative pulse-based proteins, is funded by USDA/NIFA’s Organic Agriculture Research and Extension Initiative (OREI), a program OFRF’s advocacy work aims to bolster and protect.

Dr. Thavarajah brings an extensive background in pulse breeding and an international focus to the effort to develop organic cultivars for farmers in the southeast.

“I think the international component is very important because pulse crops especially are inbred and they are not very genetically diverse. Major universities with pulse breeding programs in the US are all conventional. We need to exchange material because the material they develop for conventional is not going to work with organic. Organic is a whole different ball game.” -Dr. Dil Thavarajah

The project builds on a previous OREI grant that helped to identify varieties that worked well in organic crop rotations with sorghum. These varieties are now being evaluated to identify those with higher protein and sugar content, and better protein quality (measured both by digestibility and consumer preference). Dr. Thavarajah calls her approach “participatory breeding” that includes both consumers and farmers in the process. Interestingly, higher sugar content not only makes pulse crops sweeter and preferred by consumers, but also makes the plant more climate resilient. Having more sugar alcohols in the plants means the plants are more likely to remain healthy through drought stress, extreme heat, or cold snaps.

The project builds on a previous OREI grant that helped to identify varieties that worked well in organic crop rotations with sorghum. These varieties are now being evaluated to identify those with higher protein and sugar content, and better protein quality (measured both by digestibility and consumer preference). Dr. Thavarajah calls her approach “participatory breeding” that includes both consumers and farmers in the process. Interestingly, higher sugar content not only makes pulse crops sweeter and preferred by consumers, but also makes the plant more climate resilient. Having more sugar alcohols in the plants means the plants are more likely to remain healthy through drought stress, extreme heat, or cold snaps.

Ultimately, though, the farmer-collaborators are the centerpiece of the breeding program. “I don’t think I could be successful without my growers,” she admits. The willingness of farms like W.P. Rawl and Sons to trial new varieties and crop rotations led to successful grant proposals and may very well lead to new cultivars being released to farmers very soon. To acknowledge this, Dr. Thavarajah looks forward to releasing new varieties that bear the names and legacies of the farmers involved in the project.

Learn more about Dr. Thavarajah’s work (including advice for fellow researchers applying for OREI funding) by watching the following short video interview with OFRF, and follow her work to stay updated on the release of biofortified pulse crops for organic farmers in the southeast!

This research is funded by the USDA/NIFA’s Organic Research and Extension Initiative. To learn more about OFRF’s advocacy work to protect and increase this type of funding, and how you can help become an advocate for organic farming with us, see our Advocacy page.

Benefits of Crop-Livestock Integration

In OFRF’s 2022 National Organic Research Agenda (NORA), organic farmers and ranchers across North America shared a common concern about the lack of technical assistance and educational resources available for Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems (ICLS). Integrating crops and livestock results in numerous benefits, however the process can also lead to increased complexity, especially for farmers who must adhere to National Organic Program rules and regulations.

This series of resources focused on Crop-Livestock Integration is informed by interviews with four highly-experienced organic producers that shared their challenges, successes, and advice for others interested in integrating livestock and crops on their organic farms.

Learn about the benefits of crop-livestock integration, including reduced inputs, improvements in soil tilth and health, higher nutrient densities in food and forages, pest control in crops and livestock, decreased need for mechanical cultivation, and more.

Crop Rotations and Crop-Livestock Integration

In OFRF’s 2022 National Organic Research Agenda (NORA), organic farmers and ranchers across North America shared a common concern about the lack of technical assistance and educational resources available for Integrated Crop-Livestock Systems (ICLS). Integrating crops and livestock results in numerous benefits, however the process can also lead to increased complexity, especially for farmers who must adhere to National Organic Program rules and regulations.

This series of resources focused on Crop-Livestock Integration is informed by interviews with four highly-experienced organic producers that shared their challenges, successes, and advice for others interested in integrating livestock and crops on their organic farms.

Farmers with ICLS utilize carefully-planned rotations of crops and animals that intersect and overlap to provide benefits to soil, crop, and livestock health. Read about and see illustrations of examples of integrated crop and animal rotations developed by organic farmers.